Welcome to SENSIS, the web presence of Utrecht University’s Islamic sensory history research project! Our aim is to write a cultural history of the senses in the Islamic world, from the emergence of Islam in the 7th century CE to the 20th century. Our approach to Islamic sensory history is premised on the assumption that sensory perception is not only a physical but also a cultural act. Inspired by the ‘sensory turn’ that has enriched many areas of the humanities and social sciences in recent years, we are interested in exploring how different historical, geographical, social, and intellectual contexts determined the ways in which Muslims across the Islamic world experienced and understood sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch. In short, how are we to conceive of the Islamic sensorium, past and present? In seeking answers to this question, our research team hopes to establish and consolidate a novel research paradigm for studying the history of Islam and the larger Muslim world.

Focusing on the early centuries of Islamic history, phase 1 of this project, “The Senses of Islam,” ran from 2017 to 2022 and resulted in the publication of the multi-author handbook Islamic Sensory History, Volume 2: 600-1500 (Brill: Leiden-Boston, 2024, OPEN ACCESS). It was funded by a European Research Council Consolidator Grant (project number 724951).

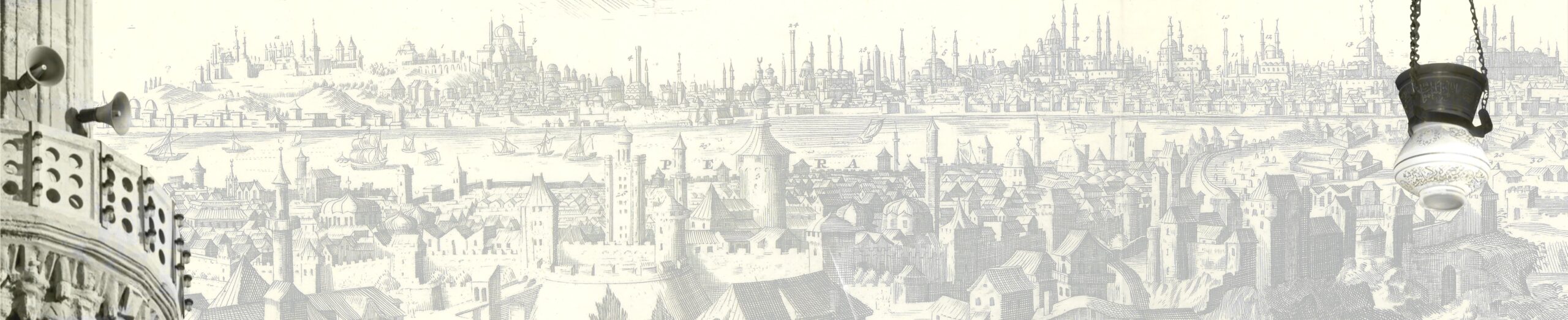

In phase 2, “Rosewater, Nightingale, and Gunpowder” (2023-2028), we focus our attention on the three early modern empires often referred to as the “gunpowder empires”: the Ottoman Empire (c. 1281–1924), the Safavid Empire (c. 1501–1722) and the Mughal Empire (c. 1526–1858). Funded by the Dutch Research Council’s Vici Grant, phase 2 will lead to the publication of the multi-author handbook Islamic Sensory History, Volume 3: 1500-2000 (Brill: Leiden-New York, forthcoming, OPEN ACCESS).

By stressing the sensory dimensions of Islamic history, our research project hopes to shed light on an understudied but essential aspect in the history of Muslim societies. Thereby, we aim to challenge common assumptions about Islam and Islamic culture, such as the idea of a ‘great divide’ between the sensory cultures of Europe and the Islamic world. In addition, we hope that our work will also enable a fresh appraisal of the non-Muslim imagination of the Orient and of Islam as the negative foil – or variously, the inspirational counterpart – of the allegedly objective, rational, and disembodied West.